Caulfield Park is Glen Eira’s largest park and is home to not only an array of sporting and recreational facilities, but is also an important habitat for many birds, fish and turtles.

Caulfield Park Lake

The lake at Caulfield Park is an important biodiversity hotspot in Glen Eira, home to many birds, fish, turtles, insects and more.

Protecting and promoting this space and the animals that live there is a joint effort with the community.

We’ve created interpretive signage surrounding the lake to share more information about the history of the environment, the native animals you’ll find in the Park and what we can all do to help protect and promote this space to support native animals.

Feeding native animals

While it may be fun to feed native animals such as birds and ducks, it does them more harm than good.

Our open spaces such as parks, bush-land reserves and gardens provide an abundance of natural foods and habitat for local wildlife.

Human food isn’t for native animals and can make them very sick — nothing we can feed them can adequately replaced their own natural diet.

we don’t feed the wildlife:

- Human food isn’t for native animals and can make them very sick potentially lead to death.

- It can contribute to them losing their ability to forage for food.

- They can become aggressive and want more food.

- Rodents like rats and mice often infest areas where animals are being fed, due to leftover food.

- Feeding areas make animals an easy target for predators like foxes, dogs and cats.

- Creating feeding areas often leads to excessive animal numbers in places too small to accommodate them.

- When animals do not contribute to the food chain by following their natural diet, it can lead to environmental problems such as a decrease of insect consumption, pest plant invasion, and loss of indigenous plants.

- If young animals are not taught by their parents how to forage for natural foods, the young risk starvation.

- The natural cycles of migration (which are largely determined by seasonal food supplies) may be disrupted when other food is readily available year-round.

- Food can become stale and grow fungi that are poisonous to the wildlife that eats it.

- Bread thrown into the waterways contributes to the high nutrient levels that promote the growth of blue green algae.

From lagoon to public park (interpretive sign)

In its earlier days, the land that came to be known as Caulfield Park was swampy, waterlogged terrain used for fishing by the local Indigenous population.

As the City of Caulfield grew, it came to be known by locals as Paddy’s Swamp and offered a watering spot for travelling livestock. As large portions of the land were drained for road construction, locals used it for recreational purposes including walking, picnicking and fishing.

The ornamental concrete lake we have today was constructed in 1976 and stands as a reminder of the park’s origins. It remained home to wildlife such as ducks, assorted waterfowl and the short-finned eel (some very old specimens of which survive) but was not regarded as a wildlife preserve.

Local children used the lake for swimming and the grounds surrounding it were planted in a European style with decorative species of exotic flora such as roses, poplars and golden elm.

Non-native ducks and geese were introduced following the lake construction. These populations, while appealing to many visitors to the park, trampled native plants and created large amounts of waste that polluted the water. They also suffered harassment and injury from off-leash dogs and frequently needed medical attention.

A lake of limited biodiversity (interpretive sign)

As local neighbourhoods grew during the 20th century, Caulfield Park offered more playing fields and sporting facilities. The lake continued to be treated as a decorative, manicured feature — a picturesque setting mainly for ducks and geese.

Introduced species, including the irresponsible abandonment of domestic pets, have restricted the numbers of native plants, birds and other animals that could thrive here. As a result, the biodiversity of the lake has been limited.

A survey in 2022 revealed an interesting mix of native species, though populations have been small.

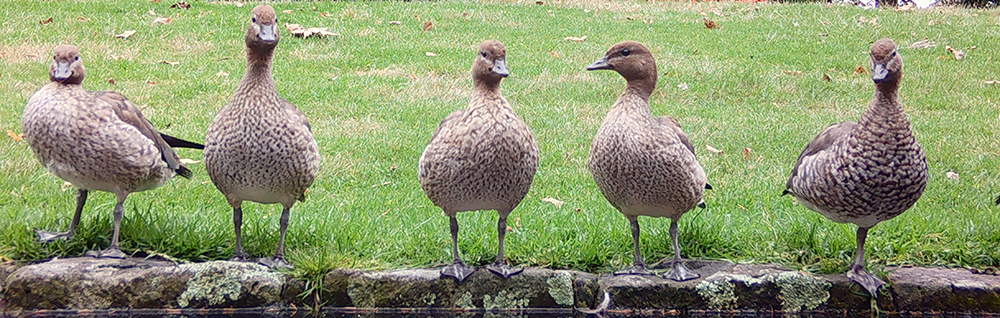

Pacific black duck (Anas superciliosa)

This species is found in all but the driest regions of Victoria. It feeds mostly on plants, but also molluscs, crayfish, aquatic insects and larvae.

Chestnut teal (Anas castanea)

The males and females have very different plumage. They make nests in tree hollows and grasslands in or near water, and feed on seeds and insects, along with some vegetation as well as molluscs and crustaceans in more coastal habitats. Populations have suffered from loss of habitat and feral animal predation.

Nankeen night heron (Nycticorax caledonicus)

These birds appear at various times at the lake according to rainfall. Feeding at night in shallow water on a variety of insects, crustaceans, fish and amphibians, they prefer to live in well-vegetated wetlands, floodplains, swamps, parks and gardens.

Eastern long-necked turtle (Chelodina longicollis)

These reptiles can live up to 50 years. They are carnivorous, feeding on fish, insects, tadpoles, frogs, yabbies and other crustaceans. When hunting, it pulls its neck under its shell, then strikes its prey, similar to the action of a snake.

Freshwater shrimp (Paratya australiensis)

This species is found in lakes and ponds, rivers, creeks and lowland streams, including lower-salinity areas of estuaries. It is usually found among aquatic vegetation around the edges of a body of water.

Billabong/slow water mussel (Velesunio ambiguous)

These hardy shellfish live in still waters, can live over 20 years and endure temperatures from 4C to 30C. They filter algae and help to keep water clean. Their tough flesh is also a traditional food source for First Nations peoples.

Diving beetle (Order Coleoptera)

Diving beetles are found in almost every kind of freshwater habitat, from small rock pools to lakes. When hunting, they cling to grasses or pieces of wood and hold still until prey passes by, then they lunge, trapping their prey between their front legs and biting down with their pincers.

Welcoming native Australian flora and fauna (interpretive sign)

By encouraging native Australian species, we can provide a sanctuary for a much broader variety of plants, animals and insects. Several new Australian blackwood trees (Acacia melanoxylon) on the island will form a canopy and habitat trees.

As we make the lake healthier and more biodiverse, we may see the following animals choose the lake as their home.

Australasian grebe (Tachybaptus novaehollandiae)

This small waterbird has two distinct plumage phases. The non-breeding plumage of both the male and female is dark grey-brown above and mostly silver-grey below, with a white oval patch of bare skin at the base of the bill. During the breeding season, both sexes have a glossy-black head and a rich chestnut facial stripe.

Little black cormorant (Phalacrocorax sulcirostris)

This is a smaller cormorant measuring 60–65cm with all-black plumage. It is a mainly freshwater species found near inland bodies of water and occasionally sheltered coastal areas.

Dusky moorhen (Gallinula tenebrosa)

The dusky moorhen feeds both on land and in water. Its diet consists of seeds, the tips of shrubs and grasses, algae, fruits, molluscs, and other invertebrates. Adults may make a quiet hissing noise when their eggs are disturbed.

Grey butcherbird (Cracticus torquatus)

This endemic species has a joyous birdsong and adapted well to city living. Grey butcherbirds feed on: invertebrates, mainly insects; small vertebrates, including other small birds and their nestlings; lizards; and occasionally fruit and small seeds.

Spotted marsh frog (Limnodynastes tasmaniensis)

A medium-sized species reaching up to nearly 5cm long. It has a grey-brown or olive-green back with darker olive-green or brown patches. It lays eggs in a foamy mass on the water’s surface which take at least three-and-a-half months to develop into frogs.

Striped marsh frog (Limnodynastes peronii)

A large species up to 7.5cm in body length. It has a brown back with dark-brown longitudinal stripes, and sometimes a cream-coloured or reddish stripe down the middle. Eggs are laid as a foamy mass on the surface of most still water bodies and can take seven to eight months to reach adulthood.

Dragonflies and damselflies (Order Odonata)

These insects are generally solitary, but sometimes appear in large numbers on structures like fences. Males are found perched on vegetation near water, on rocks or in the air. Females may be found away from water.

Spot something interesting? Let us know below

Download the iNaturalist app and share it with us.

It’s available for download on smartphones here: https://inaturalist.ala.org.au/

About iNaturalist Australia

One of the world’s most popular nature apps, iNaturalist helps you identify the plants and animals around you. Get connected with a community of over 750,000 scientists and naturalists who can help you learn more about nature!

What’s more, by recording and sharing your observations, you’ll create research quality data for scientists working to better understand and protect nature. iNaturalist is a joint initiative by the California Academy of Sciences and the National Geographic Society, and iNaturalist Australia is managed by the Atlas of Living Australia (ALA) as a member of the iNaturalist Network.